The Unreprinted: The Leap by Bill Hopkins

Why was this 1957 British novel destroyed by the publisher?

Bill Hopkins was an author from Wales who spent most of his career as a journalist, but wrote one novel in 1957. Hopkins was considered part of the “angry young men” literary movement, a loose collection of writers in the 1950s of the United Kingdom whose common trait was a dissatisfaction with traditional British society. Kingsley Amis is probably the most well-known of these with his comedy novel, Lucky Jim.

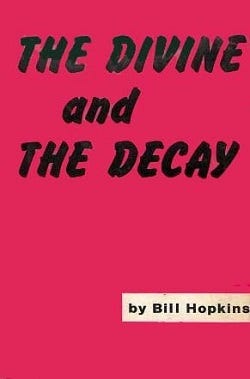

Bill Hopkins’s novel as first published as The Divine and the Decay. It was immediately met with universal disdain from critics. It was derided as poorly written and denounced as fascist. The negative press made the publisher decide the pulp the run of the novel. Hopkins had written a second novel, but after it was accidently destroyed in a fire, he decided to abandon it and concentrate on journalism.

Among the few defenders of the book was the philosopher and author Colin Wilson, who considered it an important work of moral questions. Thanks to Wilson’s clout, the book was eventually republished in 1984 under a new title, The Leap. However, it seemed to gain little attention the second time around and eventually fell out of print again.

So, what’s this book that caused such a stir in 1950s Britain about?

The Leap follows Plowart, a member of a British political party known as the New Britain League. Shortly before an election, he’s taking a vacation to a small island in the Channel. Mostly to have an alibi when his rival for leadership of the party is murdered.

Because of a fight with some fishermen from the island, he’s forced to take up residence in a disabled man’s house. There, he learns the man’s wife has been having an affair, and he’s looking to stop it for good. Plowart also meets Claremont, a woman who finds him both fascinating and repulsive for his outlook on life.

All the while, Plowart has to make more and more of an effort to hide his involvement in the assassination of his rival when a cop shows up.

Plowart is an entertainingly awful person. He’s willing to lie, cheat, steal, and murder his way to the top. He spends his nights reading about the conquerors of history. He’s convinced that he’s going to become the undisputed ruler of Britain soon.

He’s also kind of an idiot.

His philosophy and his ponderings of it are at the level of a comic book villain. He takes impulsive actions that nearly get him killed or caught constantly. He congratulates himself when circumstances save him, as if they weren’t dumb luck.

It makes for a great satire of the type of person that rises in politics, the cruelty of political power, and how little that power really matters in an indifferent universe that will sweep someone away without a thought.

The problem is, I’m not sure that’s what Hopkins intended with this book. It’s definitely not how others read it, based on the reviews I’ve seen.

I can’t really speak for most of the contemporary reviews from 1957 saw in this. If I wanted to find those, I’d probably have to go to England and dig through the newspapers archives. I can, however, understand why less than a decade after WWII, this could be considered a fascist work.

Plowart has no real political philosophy. He talks up figures like Napoleon, but also enjoys reading Marx. The platform of his party is barely mentioned, and when it is, it’s nothing but vague populism. In fact, Plowart seems completely indifferent to any form of politics, except for how he can obtain power at any cost.

That, combined with the overall pessimism of the novel, likely made critics think this was a work espousing the worthlessness of human life and how power is the only thing that really matters. I imagine a publisher in post-WWII Britain didn’t want to have a book with that reputation.

Even Colin Wilson and Bill Hopkins’s forewords to the edition I read claim it’s a book about the Nietzschean concept of the will to power and a Strinerite questioning of moral assumptions. If that’s the case, no wonder one it was dismissed as “adolescent” in its initial publishing.

Both Nietzsche and Stirner were concerned with questioning and rising above the fixed moral answers of their day, but in pursuit of new and better ways to self-actualize. Their philosophy being reduced to murdering and backstabbing one’s way into becoming a dictator is an absurdly juvenile takeaway.

It’s no wonder why some modern right-wing critics have praised it, then.

Still, I think there is a bit more going on.

Plowart isn’t exactly portrayed as being “in the right.” As I noted above, he’s often a feckless moron who gets in his own way, his arrogance is hilariously over the top, declaring himself the greatest human to ever live, and Claremont, his love interest and moral counterpart, often gets one over on him.

The final image of the book has Plowart, having been tricked into a dangerous swim in the Channel by Claremont, screaming that he’s indestructible as the fishermen he fought with at the beginning of the book leave him to drown. His only hope is a lifesaver that may or may not float towards him in time that one of the fishermen decided to lazily toss in the water.

I can’t see this as a “triumph” at all. Even if Plowart grabs the lifesaver and survives, the novel gives every indication he’s headed for a violent end, likely in prison when he’s arrested for conspiracy to murder. Even if he rises as Britain’s dictator, he’ll likely die at the hands of its people after a disastrous rule.

Is this a book that deserves to come back into print? Probably in some form. It’s certainly entertaining and works well as a page-turner, especially if you enjoy stories about characters who are terrible people. Is it some lost 20th century classic? Not really. I think critics wouldn’t have been that big on this book, even if it didn’t hit the kind of sour note it did when it was first published. I don’t think most readers would have been either.